Imagine you are working on a shipping service that exposes an API, and whenever an order is paid successfully, the mentioned API is called to create a new shipping request. On a daily basis, due to problems such as network timeout, this API receives duplicate requests. In this article, we discuss idempotency and how we can develop a reliable API that processes duplicate requests once.

How an API might receive duplicate requests

While dealing with microservices, the most unstable part usually is the network. In an application that has tens of millions of users, problems that have a one-in-a-million chance to happen occurs each day, and network failure is not an exception.

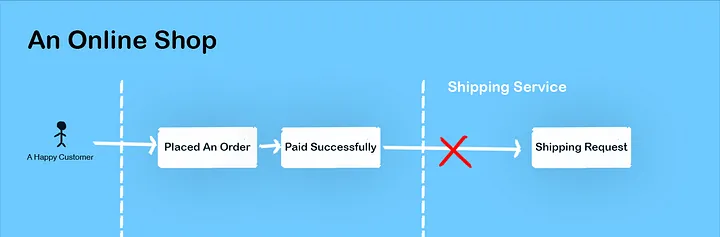

Imagine our online shop is something like this. I separated the shipping service from other services to mainly focus on it in this article. However, the problems that we mention in this article are universal, especially in important services such as payment.

Imagine, for any reason, can be network failure or timeout, the shipping request is made by another service and received by the shipping service. However, the connection between that service and the shipping service is broken, and the other service has no idea whether the request is finished successfully or not. This problem can also happen with message brokers, such as Kafka, that guarantee at-least-once message delivery.

What is an idempotent API?

An idempotent API is an API that produces the same result regardless of the number of times a particular operation is executed. In other words, making multiple identical requests to an idempotent API endpoint will have the same effect as making a single request.

Idempotent APIs allow API users to retry requests in case of network failure or other problems without worrying about creating duplicate rows in a database or charging the client multiple times.

Let’s build the shipping service

First, I build the naive version of the service, and then we test it to produce the problem that we have been talking about, and finally, we patch it using Redis.

type ShippingOrder struct {

gorm.Model

OrderID string `json:"order_id" gorm:"index"`

Vendor string `json:"vendor"`

Address string `json:"address"`

}First, I defined the ShippingOrder type, which represents the database schema. I am using Gorm, which is a Golang ORM.

type Shipping struct {

db *gorm.DB

}

func NewShipping(db *gorm.DB) *Shipping {

return &Shipping{db: db}

}

func (s *Shipping) Save(ctx context.Context, order entity.ShippingOrder) (entity.ShippingOrder, error) {

err := s.db.WithContext(ctx).Save(&order).Error

return order, err

}

func (s *Shipping) ByID(ctx context.Context, id uint) (*entity.ShippingOrder, error) {

return s.by(ctx, "id", id)

}

func (s *Shipping) ByOrderID(ctx context.Context, id uint) (*entity.ShippingOrder, error) {

return s.by(ctx, "order_id", id)

}

func (s *Shipping) by(ctx context.Context, key string, val any) (*entity.ShippingOrder, error) {

var order entity.ShippingOrder

if tr := s.db.WithContext(ctx).Where(key+"=?", val).First(&order); tr.Error != nil {

return nil, tr.Error

}

return &order, nil

}

As you can see, I created a simple repository to save ShippingOrders in a database.

I should mention that in this article, we are only focusing on idempotency, and I did not adhere to dependency injection or other clean code principles.

type PlaceShippingOrderRequest struct {

OrderID string `json:"order_id"`

Vendor string `json:"vendor"`

Address string `json:"address"`

// and etc ...

}

e.POST("/shipping/order", func(c echo.Context) error { // this API is used to place a shipping order

<-time.After(time.Second * 2)

var request PlaceShippingOrderRequest

if err := c.Bind(&request); err != nil {

return err

}

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), time.Second)

defer cancel()

createdOrder, err := shippingRepository.Save(ctx, entity.ShippingOrder{

OrderID: request.OrderID,

Vendor: request.Vendor,

Address: request.Address,

})

if err != nil {

return err

}

return c.JSON(201, map[string]any{

"ok": true,

"shipping_id": createdOrder.ID,

})

})

And finally, I created a simple HTTP API that receives new shipping orders and places them in the repository. As you might have already noticed, I made an artificial delay with the time.After method for demonstration purposes. Let’s run and test it.

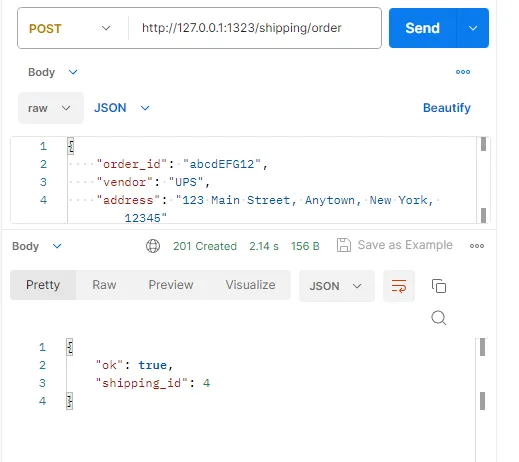

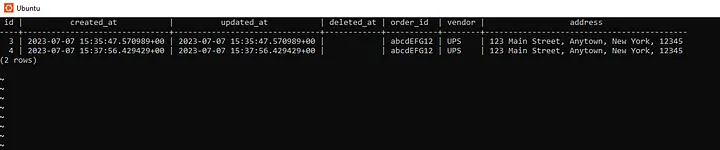

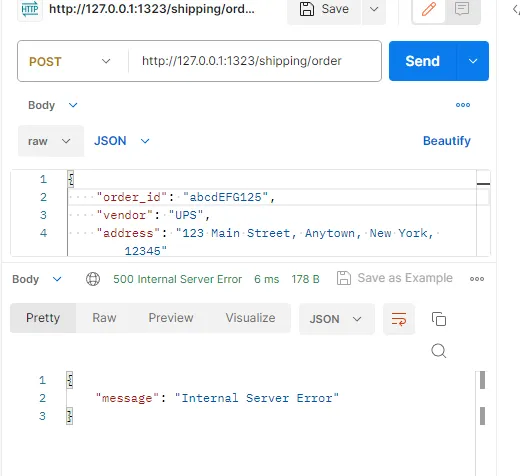

First, I made a request to the API and canceled it before the two-second timeout ended. It is like another service has called this request but, due to network problems, has not received the acknowledgment, so it retries the request. Let's check what we have in the database.

As you can see, we have a duplicate record in the database. If we do nothing about it, there will be two actual shipping requests.

There are two approaches to handle this problem:

- Avoiding duplicate requests in the first place.

- Remove duplicate rows while reading from a data source.

In this article, we only discuss the first approach.

Ensuring Idempotency with Redis

For this part of the article, I will be using Upstash’s free Redis cluster. You can use up to 10k requests per day on the free tier, which is a great place to start.

Redis is single-core by nature, which makes it a great candidate to handle atomic transactions, and we will use this feature of Redis to create a system that ensures idempotency in our system.

We need that the communication between the service and Redis be something like this: “Hey, Redis. Have you had any requests with this idempotency key? If you have not, I can process this request so let others know in the future. “

We can achieve this behavior by using NX commands in Redis. These are the type of commands that do what they do if the key is not present.

type Redis[T any] struct {

client *redis.Client

}

func NewRedis[T any](rdb *redis.Client) *Redis[T] {

return &Redis[T]{client: rdb}

}

// Start returns the executed result and true if the idempotency key is already executed. Otherwise, returns empty T and false

func (r *Redis[T]) Start(ctx context.Context, idempotencyKey string) (T, bool, error) {

var t T

tr := r.client.HSetNX(ctx, "idempotency:"+idempotencyKey, "status", "started")

if tr.Err() != nil {

return t, false, tr.Err()

}

if tr.Val() {

return t, false, nil

}

b, err := r.client.HGet(ctx, "idempotency:"+idempotencyKey, "value").Bytes()

if err != nil {

return t, false, err

}

if err := json.Unmarshal(b, &t); err != nil {

return t, false, err

}

return t, true, nil

}

func (r *Redis[T]) Store(ctx context.Context, idempotencyKey string, value T) error {

b, err := json.Marshal(value)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return r.client.HSet(ctx, "idempotency:"+idempotencyKey, "value", b).Err()

}

As you can see, we have two methods. Start and Store. When the start method is called, it checks whether the idempotency key is already processed or not. If it is processed, it returns the stored value. Otherwise, it locks the idempotency key and allows the current request to calculate it.

- If the val() is true, it means Redis has stored the value. Otherwise, the val() would be false.

- We are saving the process and the result of the idempotency key in a hash with two keys, status, and value.

e.POST("/shipping/order", func(c echo.Context) error { // this API is used to place a shipping order

var request PlaceShippingOrderRequest

if err := c.Bind(&request); err != nil {

return err

}

//////////// check whether the request is already proccesed

stored, has, err := shippingIdempotency.Start(context.Background(), request.OrderID)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if has {

return c.JSON(200, stored)

}

////////////

<-time.After(time.Second * 2)

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), time.Second)

defer cancel()

createdOrder, err := shippingRepository.Save(ctx, entity.ShippingOrder{

OrderID: request.OrderID,

Vendor: request.Vendor,

Address: request.Address,

})

//////////// saving the final value for future requests

if err := shippingIdempotency.Store(context.Background(), createdOrder.OrderID, createdOrder); err != nil {

return err

}

////////////

if err != nil {

return err

}

return c.JSON(201, map[string]any{

"ok": true,

"shipping_id": createdOrder.ID,

})

})

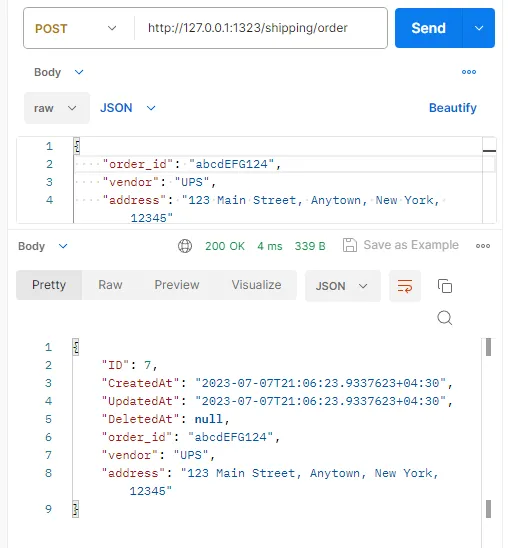

Let’s run and test the changes:

Now, it doesn’t matter how much you send this request. You will receive the same response without any duplicate rows in the database.

There is still a huge problem!

Do you remember the two-second sleep that I added to the code previously? It is an exaggerated version of a problem that might happen. What would happen if the duplicate request is made within that two-second duration?

The service will crash! But what is the reason behind it? in this two-second period, there is not any value stored in the database, and the first request has not finished processing the request. We have two options:

- Drop the second request

- Wait for the first request to finish and then show the result.

The second option is way more fun and makes the service more reliable. To achieve it, we can use Redis pub/sub and listen for the idempotency key to change and then show the result to the client. Working with Redis pub/sub is fun, and I will talk about it in future articles.

Conclusion

In many cases, idempotency is already achieved by following best practices. For instance, not making any changes to the database or cache ensures GET requests are idempotent. In this article, I tried to cover some of the basics of idempotency and did not cover packages or libraries; instead, we built it from the ground up. I encourage you to read more about the Idempotency-Key header in HTTP requests.

Golang Redis Microservices Idempotency API